What are minerals and vitamins?

It’s important to cover what vitamins and minerals are because it’s a subject that people rarely consider. This often occurs when scientific words enter common vernacular, but words have specific definitions and these definitions are important. Without understanding the definitions fully, you are never truly a master of a topic, so before we start listing things we will describe what exactly minerals and vitamins are.

Minerals

Minerals in nutrition are the chemical elements present in tissue once it has been burned. Dietary minerals could be consumed in the form of an inorganic salt like sodium chloride (table salt) or potassium chloride which you might find in a sports drink, or it could be part of an organic compound – like the magnesium contained in chlorophyll which is what makes your greens… green.

Minerals can be broken into two categories. There are six which we require in gram or near-gram amounts, and nine which are trace elements needed in tiny amounts. This is important, because although your body can somewhat regulate the minerals that we require in larger amounts, the trace minerals can become severely toxic if over-consumed.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic compounds essential for an organism to function. You already know that organic means that it contains carbon, and you know that essential means that it cannot be endogenously synthesised, but this also tells you that a vitamin is categorised according to the organism and not because of any common trait that all vitamins share (other than their carbon atoms). Vitamin C, for example, is a vitamin in human nutrition as we cannot synthesise it, but it’s not a vitamin for dogs because they can.

Like minerals, vitamins are also separated into two categories, the four fat-soluble and nine water-soluble forms. Water-soluble forms are very difficult to overdose on and cause any serious harm because they can be expelled easily enough through urine. Fat-soluble vitamins can indeed be overconsumed and may lead to health problems if this overconsumption is chronic. This tables gives you an overview of what we mean:

| Fat-soluble | Water-soluble |

|---|---|

| Excess stored in fat tissue and liver | Excess excreted urine |

| Decreased chance of deficiency | Increased chance of deficiency |

| Increased chance of excess | Decreased chance of excess |

Nutrient needs: how do we define them?

Deficiencies in any of the above nutrients may lead to a decline of any biological function, from immune function to energy production to nerve signalling. As mentioned, some of them may cause serious problems if overconsumed as well, by either blocking/preventing the absorption of other minerals and therefore causing a deficiency, or simply by becoming toxic and having direct adverse effects. This is one of the main ways by which unbalanced dietary practices (typically those which hugely emphasise one nutrient or food group, or which eliminate another) may cause problems. We will explain this further in the sections on the specific nutrients, but consider that a diet which is intentionally very low sodium can lead to problems with muscle cramps and even heart function, while a diet which overemphasises organ meats can lead to a harmfully high intake of vitamin A.

It is because of this that, if nothing else, we hope you take from this module a further clarification of the importance of balance and variety within nutrition. We will summarise it by placing into context the real-world approach recommended for ensuring sufficiency, but before we do, we will explain in specific terms what the theoretical amounts are which you need to consume to be in perfect health. However, before that we need to show you how these figures are determined.

The recommendations we will give are those recommended presently by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN (FAO). These two bodies had initially set out guidelines in 1974 but then in 2004 with the publication of “Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition – Second Edition” they revised their recommendations and most of them had increased. This, the writers of the report claimed, was due to a multitude of reasons. Firstly, in the years between the reports the body of scientific literature had expanded dramatically, but on top of that the criteria for setting the RNI (Recommended Nutrient Intake) had also changed. Initially the RNI was supposed to be that which would meet the basic nutritional needs for 97% of the population, but the definition of ‘meeting basic nutritional needs’ is open to interpretation. Previously the criteria used to determine basic needs was considered in the context of widespread deficiency in developing countries, but the question then remains – what is deficiency?

It’s highly unlikely that most individuals will ever die directly of a micronutrient deficiency. It does happen, of course – some micronutrient deficiencies can be fatal, but generally speaking death isn’t the consequence, and as such we can’t simply take ‘you die if you eat less than this’ as a minimum amount. What often happens is that a deficiency will lead to a clinical ailment. As an example, long-term vitamin C deficiency can lead to the bleeding condition scurvy and long-term vitamin D deficiency can cause rickets. Vitamin A deficiency which can be common in developed countries can lead to blindness, too. None of these conditions are fatal, but they are extremely damaging to someone’s health – but again, is avoiding illness what we really want to do, or can we do better?

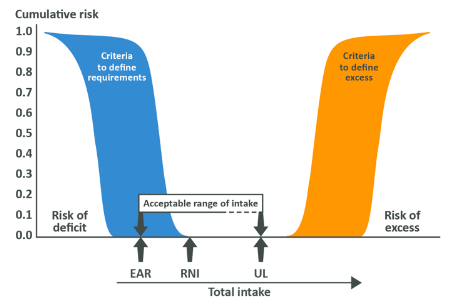

Vitamin and mineral intakes can be considered on a spectrum from fatal deficiency to wasteful, harmful or even fatal overconsumption. Somewhere along that spectrum there is a point where you will not die but may contract a clinical deficiency, somewhere there is a point where you are no longer at risk and somewhere along the spectrum is an intake which could be considered ‘optimal’. The more up to date recommendations take in to account that the level which will ‘avoid clinical deficiency’ may not always be the intake level which will avoid all negative consequences of low intakes.

Each nutrient has, therefore, a few different numbers attached to it. There’s the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) which is ‘the average daily nutrient intake level that meets the needs of 50% of the ‘healthy’ individuals in a particular age and gender group’. Then there is the Recommended Nutrient Intake which is the EAR plus two standard deviations (a standard deviation is the amount a typical individual in a group might differ from the average of that group) which basically means the EAR plus a bit, where the ‘bit’ is relative for the nutrient. This will ‘meet the needs of almost all apparently healthy individuals in an age and sex specific population group’.

If relevant, a nutrient can also be given a TUL or Tolerable Upper Limit, which is the maximum amount which could be consumed by 97.5% of the healthy individuals in a given age and sex population without causing adverse health effects. For most nutrients, the intake/excretion level is regulated well within the body and therefore most nutrients (with some notable exceptions) are unlikely to be consumed excessively from foods – the problem comes when supplements are taken which provide unnatural intake levels. This will be explained nutrient to nutrient, however.

Some nutrients may also be given a protective intake level. This is a number above the RNI but below the TUL which, when consumed, may have additional beneficial effects.

“Risk function of deficiency and excess for individuals in a population related to food intake, assuming a Gaussian distribution of requirements to prevent deficit and avoid excess”.

(Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition. (2004). 2nd ed. World Health Organisation, p.3).

Alongside the figures presented by the WHO, we will also provide the intake recommended by the UK Government at the time of writing this document in the Eatwell Guide. We recommend you stick with the UK Government set minimums as they reflect the most up to date information and the UK environment. Not all vitamins will have all of these values as the recommendation may not exist.

Recommendations for micronutrients are generally presented as population-based RNI’s and are not intended to define the daily requirements for an individual. While a healthy individual consuming between the RNI and UL will minimise their risk for long-term micronutrient deficiency or overconsumption, this does not necessarily mean that it would be the correct recommendation for high-level athletes engaged in extreme forms of exercise (an hour or so per day, 3-5 days per week doesn’t qualify you for this category) or individuals who do not meet the criteria for generally healthy (which amounts according to the WHO/FAO report to someone who presents with an absence of disease, absence of existing nutrient deficiencies or excesses and normal bodily function). Those with any internal health complaints should speak to a dietician qualified in the specific area relative to them. In the previous module, we gave recommendations which could be individualised a little bit according to a person’s height and weight, but no such recommendation is possible with most micronutrients, simply as the information which would be needed to do so is largely not available.

If, however, you are generally healthy, not a high-level athlete, and haven’t been either eating liver four times per day for the past year or avoiding anything that isn’t water, white bread and jam, the following micronutrient recommendations should apply to you!

As a final point, the amounts expressed will be in a few different units, please use this table for reference so you know what on earth we mean by the different abbreviations.

| Unit | Abbreviation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Gram | g | The weight of 1 millilitre of water. 1, 1000th of a kg |

| Milligram | mg | 1000th of a gram. 0.001g |

| Microgram | ug | 1000th of a mg, 1,000,000th of a g. 0.001mg or 0.000001g |

| International unit | IU | The conversion of IU to standard measures depends on the thing being measured. While IU may be mentioned for some nutrients, the amounts stated for the various intake levels can be given in any of the above units |

Let’s start with the vitamins, specifically the fat-soluble ones.