Habit loops and cravings

To bring all of the above information together in a simple format, consider that habits can be thought of as behaviours engaged in via a ‘habit loop’. A habit loop is a very simple concept, namely that a habit follows the pattern of cue > routine > reward. An environmental cue initiates a well-rehearsed routine which is associated with a reward remembered as a result of that routine.

Though the reward may or may not be associated with your current values, it is a reward nonetheless (drug addicts still get a reward stimulus from their ‘fix’ when they are quitting, and overweight people still get a hit of dopamine when they eat an unplanned dessert during a fat loss effort). What we have only tentatively hinted at so far, however, is that the dopaminergic reward associated with an action is, after sufficient repetitions of that action, not actually experienced upon performing the activity. Instead dopamine is released BEFORE you do something rewarding, in order to create excited and motivated anticipation – which then leads you to complete the routine you were going to complete. Because of this early release, some interesting things happen that can be best explained by introducing another series of experiments; this time from the Laboratory of Dr. Wolfram Schultz, professor of Neuroscience at the University of Cambridge.

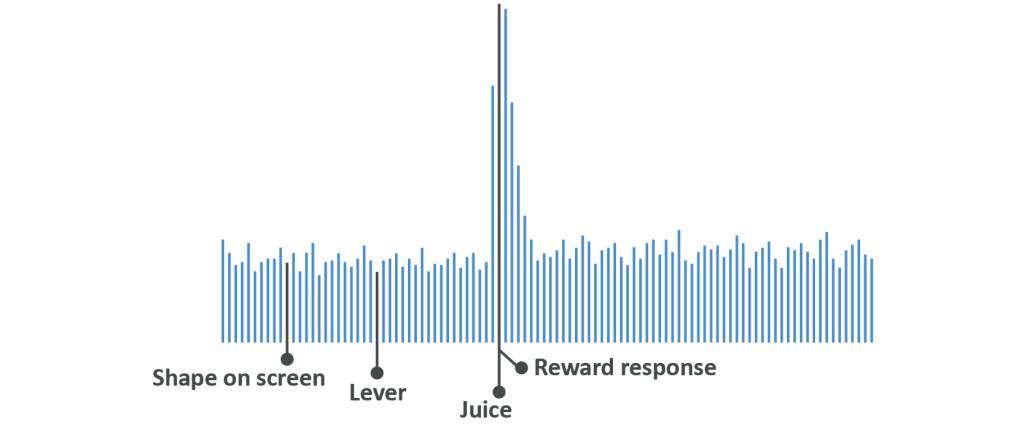

Schultz performed his experiments using a monkey called Julio, who was placed in a chair in front of a lever attached to a TV screen. On the screen, various shapes would appear and, if Julio touched the lever as a shape was showing he would be given some sweet blackberry juice as a reward. The below chart indicates activity in the reward centres of his brain at various time points in the experiment. Dopamine activity is low while the shape appears and when he touches the lever, then it increases dramatically upon being given juice.

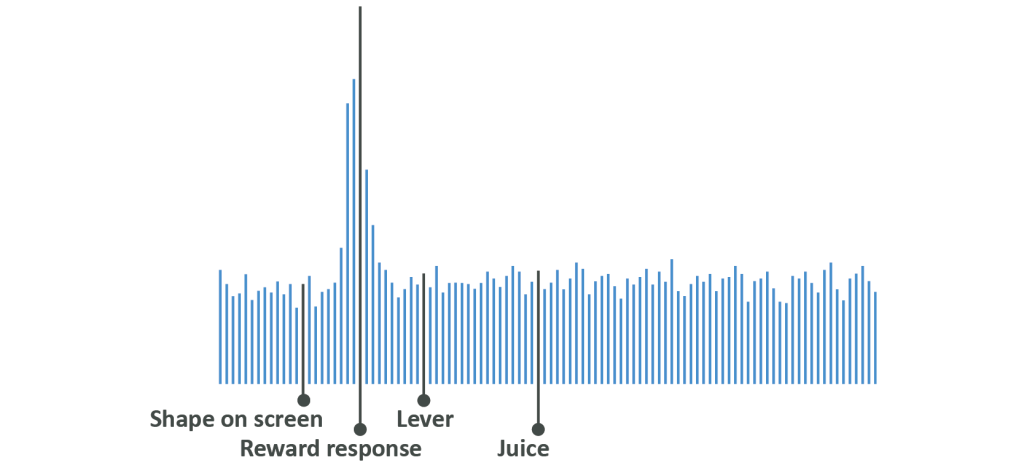

Once this habitual activity became well-engrained, however, the timing of this response was different. Rather than dopamine being released as a reward for drinking juice, it started to be released upon seeing the shape on screen (the cue).

If Julio was then given his juice he remained engaged in the task and happy, but if he was given watered down juice or nothing at all he became agitated, aggressive or displayed signs similar to what could be described as depression.

What Julio was experiencing was a craving. He had learned that a given cue resulted in a given outcome provided he executed a routine, so upon seeing the cue his brain started to want its reward.

If the reward didn’t come then cravings set in. We need to place this in context with what we know about the unchangeable nature of habit loops, too – our brain ties a cue to a reward which it expects, and if we are on autopilot we will simply robotically perform the routine needed to get the reward we want. If, however, we do manage to engage our more executive brain functions and intentionally override our habits in order to achieve a goal which we value more then we get cravings – and because those habit circuits are hardwired and very difficult to change, it is not a reasonable course of action to simply try to ignore what it is that you want.

Because of this, mindfulness and awareness of habits should not be used to resist action or exercise the force of will often referred to as willpower. We cannot delete habit loops and we cannot ignore them forever, so we must overwrite them. To close this module, we will describe the most potent methods of doing this, altering your routines and altering your environment.