Beta alanine

Much like creatine, beta alanine is a naturally occurring metabolite found in muscle tissue. It’s a non-proteogenic amino acid (unlike the 20 noted already it cannot be incorporated into proteins because it is not coded for by any genes) that is either produced in the liver, endogenously, or consumed in the diet via poultry or meat.

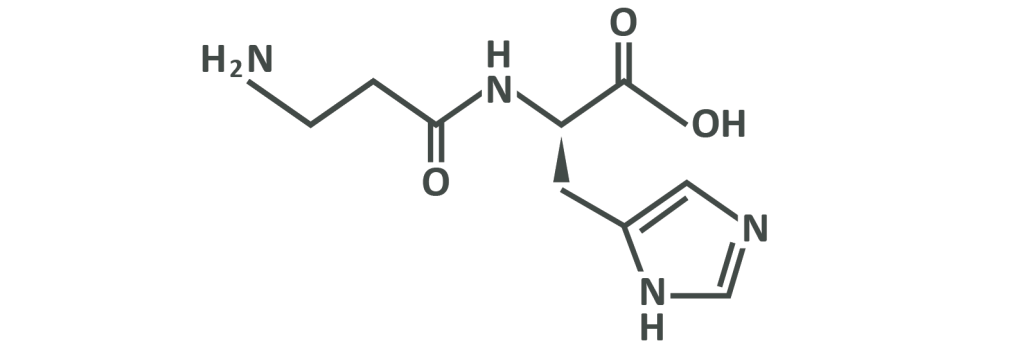

Its key role is as the ‘rate limiting’ factor in carnosine production. Carnosine is a dipeptide used in a multitude of physiological functions, made by combining beta alanine and L-histidine via the action of carnosine synthase enzymes. Beta alanine is the rate limiting factor because serum levels of BA are always lower than levels of L-histidine, and so supplementation of BA leads to an increase of stored carnosine. The enzyme carnosinase which is responsible for breaking down carnosine to its constituent parts is expressed in the blood and some tissues but not skeletal muscle – meaning that while beta alanine supplementation increases carnosine levels in the muscle (where it is synthesised), oral supplementation of carnosine directly leads only to an increase of carnosine catabolism in the blood.

Supplementation with beta alanine, in fact, leads to an increase in skeletal muscle carnosine of up to 80% after 10 weeks. So, what’s the fuss about carnosine?

Reflect back on the process of anaerobic respiration – glucose undergoes glycolysis resulting in the production of 2 pyruvates and free H+ ions. Those ions would ordinarily be ‘picked up’ by NAD+ and carried to the electron transport chain but as oxygen is not available that isn’t possible. As H+ ions build-up during anaerobic activity, they lower the cell’s pH, making it acidic. This is what causes ‘the burn’ and leads to a rapid onset of fatigue which ultimately ends a bout of intense exertion.

Where carnosine comes in is at this point. Carnosine has what is known as an imidazole ring that contains 3 carbons, 2 nitrogens and 4 hydrogens, and which is capable of picking up those stray H+ ions to render them inert. This helps to buffer intracellular pH and hold off fatigue. When studied, supplemental Beta Alanine leads to a reduction in exercise induced acidosis. This is the primary reason carnosine is important but this is not the only role it plays. Carnosine can also neutralise free radicals (reactive oxygen species/ROS) and prevent their production by interacting with some of the intermediary metals (iron and copper) responsible for some amount of the ROS produced during exercise.

In short, beta alanine increases muscle carnosine levels, and that carnosine helps performance in physical activities lasting around 60-240 seconds, but not in those lasting under 60 seconds as acidosis is not likely to be the primary cause of exhaustion here.

All of this translates to a few notable performance improvements including:

- Improved time to exhaustion in cycling trials by around 13-14%

- Improved time to exhaustion in running by around 8-15%

- Improved performance in trials taken to voluntary exhaustion (perhaps a more important metric, as this is more likely to be important in free-living situations)

- Greater improvements in time to exhaustion post 6 weeks of interval training using a beta alanine supplements

- Improved 2000m row time

- Delayed neuromuscular fatigue in sprint cycling

- Improved markers of fatigue and therefore greater volume performed in very high volume resistance training. This is most likely to reflect well on Crossfit or similar endeavours, as again acidosis isn’t often the key limiting factor in standard resistance training. As noted above, however, combining BA with creatine may improve the total effect of both in terms of strength accruement

There are no known long-term side effects of beta alanine supplementation. It is also worth noting that beta alanine has some antioxidant properties meaning that it could be beneficial for general health and disease prevention assisting with improving exercise capacity and performance. The only thing that should be discussed is the short-term unpleasant side effect caused by supplementation known as paraesthesia. This is a tingling of the skin caused by interactions with histamine receptors (usually activated to make you itch if allergic to something or similar). This is harmless and temporary but possibly unpleasant – it can be mediated by breaking a daily dose into 2-3 doses per day or it can be taken with food.

The ideal dose is 4-6g per day, for at least 2-4 weeks. The threshold dose seems to be around 179 total grams for maximising saturation, meaning that it would take around 4 weeks at 6 grams or 6 weeks at 4. After this, the maintenance dose appears to be the same, 4-6g per day.