Food and nutrient demonisation

One of, if not the main reasons that flexibility isn’t mentioned in most mainstream diets and why it can seem so counterintuitive is that human beings have a natural tendency to create dichotomies when we think about things. Everything is black or white, good or bad, dangerous or safe and this includes foods which we seem to think of as diet friendly or fattening – which doesn’t really make a lot of sense because context is always key.

There is no single foodstuff which, when consumed, will cause immediate negative health effects in most realistic portions. Barring trans fats there are very few foods which can cause chronic negatives, either. Some notable exceptions to the chronic negative effects rule are:

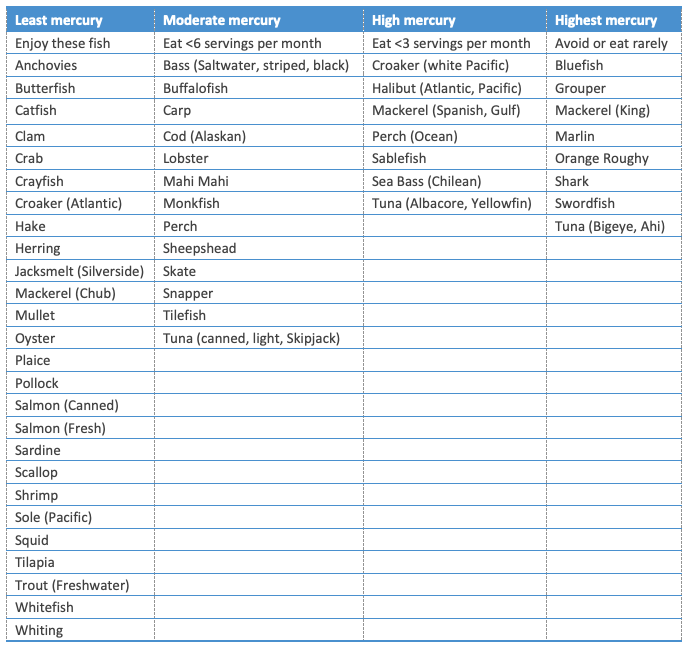

Fish which is high in mercury

Swordfish and certain breeds of tuna can contain a lot of mercury which can lead to mercury poisoning and should therefore be kept to once to twice per week depending on the specific case. This is because larger fish are at the top of the food chain, meaning they eat smaller fish and accumulate the mercury which the small fish have eaten across the rest of that chain.

A database of fish by mercury content can be found below, acquired via the NDRC at the time of writing in 2017.

Saturated fats

As discussed in module 2, saturated fats may not be the demons which they were once hypothesised to be, but this does not exonerate them entirely and it does not mean that we should actively seek to eat more of them. At least part of the controversy here stems from the fact that, as you have learned, saturated fats are just fatty acids with no double bonds in the chain, which means that there is a wide range of potential molecules to which this general name could be assigned. Stearic acid appears to lower LDL whereas palmitic acid and myristic acid appear to increase it. To confuse things further an adequate intake (in one research paper 4.5% of calories) of the Omega 6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, linoleic acid counteracted the negative effect of palmitic acid.

Though this is very obviously a complex issue and one where there is still a lot for researchers to uncover, the clear answer is that it appears a high intake of saturated fat is associated with an increase in your risk of cardiovascular disease, and the LDL and total triglyceride raising properties of these fatty acids is likely to play a role in this. A good approach here is to focus your general diet around whole foods, including lean meats, whole eggs and whole dairy which does not appear to increase risk to nearly the same degree as other foods despite its saturated fat content (with the exception of butter which does appear problematic when consumption is high) and then, if additional fats are needed, getting these from monounsaturated sources wherever possible. If, however, you are planning to eat out once a week and have the burger, this is unlikely to be an issue.

Trans fat

Artificial trans fat containing foods are still a good idea to avoid. Beyond that, though, provided you are adhering to a primarily whole foods diet, small deviations from this aren’t really an issue. Some common foods which are banned on diets, and the reason you don’t need to necessarily fear them are:

Sugar

It is associated with weight gain but it’s association is tied to an increase in energy intake. When sugars are added to a diet in place of other calories (so provided you are at calorie balance, or the calorie balance you need to be at to reach a goal) this isn’t really a problem. Being that, as you learned in module 2, all carbohydrates are broken down into monosaccharides before absorption, this makes a lot of sense – table sugar is not special or different in this regard, so it’s impact on health is largely the same. Notably, an increased intake of fructose alongside chronic overeating can be problematic so it’s likely a good idea to limit added sugar intake while eating in a calorie surplus, but this is, at least theoretically, largely mediated by being highly active and avoiding becoming overweight.

Similarly, though it is often claimed that diabetes or insulin resistance is caused by sugar intake, this is not the case, with diabetes having a multitude of causes including genetics, lifestyle and total energy intake. Sugar is highly palatable, and high-sugar foods are often calorically dense so consuming them excessively is not likely to be the smartest way to set up a balanced and long-term diet, but it would be more prudent to consider your energy and vegetable intake before your sugar intake if you are looking to avoid negative effects often claimed to be lead to via consuming too many monosaccharides.

As a practical recommendation, don’t be concerned with sugars from whole fruits or unsweetened dairy, but be mindful of foods with added sugars or concentrated sugar sources like honey and maple syrup.

Artificial sweeteners

These are non-nutritive compounds including aspartame and sucralose which are added to foods and beverages to increase their taste without adding calories – typically seen in sugar free fizzy drinks, but present elsewhere too. These have been blamed for, amongst other things, headaches, nausea, ‘brain fog’, insulin resistance, obesity, joint pain, Alzheimer’s and cancer but as yet there is no link between these compounds and these effects in randomised, controlled trials – despite a lot of looking. In fact, swapping diet drinks in place of regular drinks is an effective calorie reduction tool.

These compounds can be considered to be safe for consumption in any amount which you would realistically manage, but that doesn’t get them off ‘scot free’. First of all, some people may experience transient symptoms. These are very likely to be a result of a placebo effect but they exist nonetheless and if you are one of these individuals, the simple answer is to abstain from consumption. Beyond this the main issues surrounding artificial sweeteners are:

- Regular consumption of artificial sweeteners may alter your food preferences and make it harder for you to avoid sweeter foods

- Drinks with artificial sweeteners are still acidic and may not be great for dental health

Beyond that they are safe, and while our position will always be that water is the best thing to hydrate yourself with, drinking 1 can of artificially sweetened soda per day is unlikely to cause harm and could be an enjoyable inclusion to a balanced diet.

Liquid calories

Drinking your calories has always been a contentious point for very good reasons. Firstly, we would like to state that here we are talking specifically about fruit juices, milkshakes and regular soda rather than unflavoured milk which is a highly nutritious foodstuff or protein shakes/homemade smoothies.

The key problem with sweetened beverages and fruit juice is that they pack a lot of calories but little or no nutrition and, crucially, no impact on subsequent calorie intake. One study found that participants who were given jellybeans reduced their calorie intake later in the day to compensate but when the same amount of sugar was delivered via sweetened beverages there was no compensation (some people increased their intake relative to baseline). Sugar-sweetened beverages are likely to be a significant contributor to global obesity.

Fruit juices (home-made or other) are likely to exert similar effects due to being high in free sugars and low in fibre, and while smoothies may be far better in this regard it’s crucial to be cognizant of the total amount of energy you add to the blender because half a pint of milk, 3 pieces of fruit and some nut butter is hard to eat but very easy to drink. With all of that said, the impact these beverages have is purely due to their calorie load and their impact on subsequent calorie load (or lack thereof), so if a small amount is factored in to someone’s daily intake, this is not an issue.

Alcohol

Moderate alcohol consumption would fall in line with the above. Alcohol is a very complex topic and the Body Type Nutrition Practical Academy course covers it in great detail if you are interested in alcohol metabolism and its impact on body composition and health. For now, we recommend you stick with the UK government guidelines of drinking no more than 14 units per week, and no more than 2-3 units per day for women or 3-4 for men.

Alcoholic drinks provide a significant amount of energy (a pint of typical lager, beer or cider will contain around 200kcals, a large glass of wine (250ml) around the same, a shot of hard liquor will provide around 70kcals with many cocktails being considerably higher). Furthermore, alcohol’s ability to dampen your capacity to make healthy choices by resisting the temptation of highly caloric foods, it’s potential impact on your activity levels and food intake the day following a large intake of alcohol, pose a big problem if this is not moderated.

Beyond this, outside of genuine health problems you experience as an individual, and outside of hyper-palatable foods which you personally find difficult to moderate, no foods should be considered out of bounds. By focusing on the large issues (calorie balance, macronutrient intake, food choice for the vast majority of your diet, hydration, fibre and micronutrient intake), the small issues such as health problems brought about by sugar or the occasional saturated fat laden indulgence become far, far less impactful.

While these are not the best choices and should never be considered the backbone of a diet, it’s important that you place them in context rather than judging them as good or bad.

Tracking and adherence flexibility

It’s often the case that people are on or off their diet, but this mentality may not be the most beneficial one you could adopt for your psychological wellbeing or your long-term success. After all, it’s not necessarily reasonable to expect yourself to spend the next 365 days tracking every gram of food you eat and making perfect food choices at every opportunity. You are human and sometimes you need to let go. Here is where a broader sense of flexibility comes in. Firstly, consider that you do not need to use the same tracking method all year long; there are times when accuracy is more important and there are times where sustainability is more important. Your overall approach to food needs to be one which you can stick to for the rest of your life but that is not true of the 12 week diet you decide to use in order to get in shape for your holiday. Pick your battles. Perhaps you use level A tracking for most of the year and then level C2 tracking with every macronutrient accounted for until you jet off – this is loose tracking when appropriate and ‘tightening up’ when needed.

Moreover, you could think about the 80-90% adherence principle mentioned above not only in terms of food choice but in terms of adherence. Having two days per month where you go for a meal with friends/a significant other and eat whatever you want is very unlikely to impact on most goals that people have and doing it can be a nice break from the norm. Yes, you will eat more on these days than usual, but as we mentioned a number of times in module 1 – weight loss and gain doesn’t happen in 24 hour cycles so it doesn’t matter so long as the rest of the time is dealt with appropriately.

We then need to look at tracking accuracy within every method. In the last module we discussed the inaccuracy of food labels and the potential for leeway. This should tell you that looking to hit your calorie or macronutrient intakes every day too perfectly is a waste of time and mental energy that could be spent elsewhere. It’s far better to aim for ranges than it is for finite numbers. The loftier your goal is, the closer your ranges may be (so while getting towards the last 2 weeks of your pre-holiday diet you may have a 5g up or down range attached to each macronutrient goal and a 50kcal up or down range on your calories, but then for the rest of the year these may quadruple) but no matter what a range should exist to make hitting your recommended numbers physically possible.

Finally, to close this module, we wish to say the that most people can reach a healthy weight, and even get close to beach-body shape using level A tracking and some common sense around their adjustments. More than this, those who use level B or C can often shift to level A after a short while because they know what their needs are and how to meet them with food. Nutrition is important but focusing on nutrition should not take up a huge amount of your mental energy or daily time because the accuracy with which you manage it is limited in the best of cases, and the impact that each detail has on the final result diminishes with every step you take.

Getting your calorie intake and food choices in place will get you 80% of the way there, adding some protein portion knowledge may add another 10%, and then after that you’re talking small details. Get the big rocks in place and it all falls in line.

In the next module we will be discussing sleep, a seemingly unrelated but actually hugely important factor in your nutritional approach. If you don’t sleep as much as you should you will be hungrier, you’ll have stronger cravings and thus a diminished ability for resisting temptation, meaning that everything gets far harder than it needs to be.