Food labelling

The best place to look is a food label. Almost all foods in the UK must have labelling of some form or another, with back of the packet nutritional information being mandatory, and the following being optional labels which most, but not all, companies will use:

- Front of pack information, possibly in a traffic light system

- Nutrition labelling for non-pre-packed foods such as loose fruit or vegetables, or fresh produce/meat at a supermarket counter

- Calorie labelling for alcoholic drinks

There are also notable exceptions with the following companies not needing to use nutritional labels:

- Foods produced by small companies who predominantly sell direct to consumer (defined as those with fewer than 10 employees and a turnover of less than £1.4 million)

- A local retail establishment meaning one who exclusively supplies to their own county and the larger one of any neighbouring counties

Unlike in the past, current legislation around food labelling is very strict and companies can incur enormous fines if they are found to be giving false or misleading information on their packets as this constitutes misselling and fraud.

Some examples of information that must be given are:

- Many food names are protected, meaning that, for example, anything referred to as chocolate must have a specific amount of cocoa solids (otherwise it must be ‘chocolate flavoured’)

- In order for a sausage to be named as such, there is a minimum meat inclusion which therefore limits fillers

- If expensive products are padded out with cheaper ones (such as diluting olive oil with cheaper vegetable oils) then this must be clearly stated and the product is not able to be labelled as being the expensive ingredient

- Meats containing water or fillers must be labelled as such and misstating the amount of, for example, meat in a burger is also an offence

- Ingredients are listed in order of inclusion. A juice that lists apples, grapes, kiwi and blueberries, will therefore contain more of the cheaper fruits. This can help you to make a more informed decision

According to The Food Labelling Regulations 1996, foods must be marked or labelled with certain requirements such as:

- The name of the food

- A list of ingredients (including food allergens)

- The amount of an ingredient which is named or associated with the food

- An appropriate durability indication (e.g. ‘best before’ or ‘use by’)

- Any special storage conditions or instructions for use

- The name and address of the manufacturer, packer or retailer

- The place of origin (where failure to do so might mislead, for example stating a chocolate is from Peru when it isn’t, or a coffee is from Kenya when it isn’t)

As you can see, the label is a trustworthy source of information and so it’s your best practical means of ascertaining what you are eating, and what’s in it.

How to read a label

In the UK, there are three different areas of the food label to which you need to pay attention to the traffic light information on the front as well as the print information there, and the text/table on the back. Let’s discuss each in order.

UK traffic light labelling

The first place to look on a food label in the UK is the front of the packet where you will see the traffic light information. The idea behind this is quite simple – it allows you an ‘at a glance’ understanding of the food in your hands and can help you understand some of what you need to know, namely whether a food is low, medium or high in a given nutrient which the UK Food Standards Agency deems important. Each label will tell you the sugar, fat, saturated fat and salt per serving of food and give it a colour rating. You should notice that a red light is given to something which denotes more than ⅓ of your recommended intake per portion, or 40% of your salt intake per portion.

Note: Salt is calculated by multiplying the total sodium content by 2.5 according to UK law.

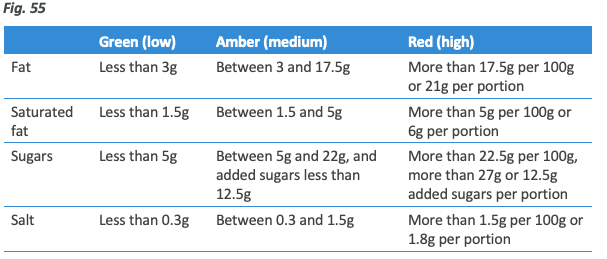

For each nutrient, the calculation is done as follows, per 100g unless indicated:

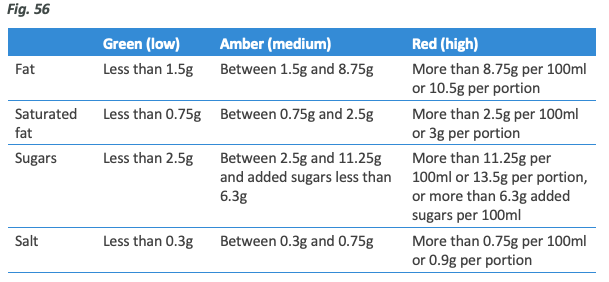

For drinks the rules are slightly different. These values are per 100ml:

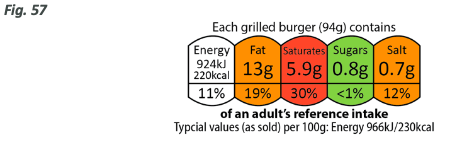

This is an excellent starting place. You can immediately see roughly what a portion of any food contains what is in it. Historically information was mostly expressed as ‘per 100g’ but if you are planning to eat half of a 350g packet, it’s not practical to be able to do the maths in your head while stood in the supermarket. Let’s look at an example packet:

Already it’s likely that you can see the value in looking at the information in this way. From a 10 second glance, you can see the caloric value (which is generally presented as a percentage of the recommended calories for the average female) and the amount of each of the four nutrients contained within the food. You can also see what a suggested portion is. The reason that these figures are then put in a traffic light code is because:

- Doing so allows you to very quickly identify whether something is ‘high’ in something

- It places the numerical values in context. Most people have not done this course and thus will not know how much saturated fat is a good idea to eat, rendering 5.9g a meaningless number. This gives that number meaning

So that’s the positives, but what about the negatives? No system is perfect and this is no exception to that rule.

Firstly, it doesn’t give you any protein or carbohydrate information, meaning that it’s incomplete. This of course doesn’t really matter being that the rest of the information is available on the rest of the label, but it does mean that this information alone isn’t enough to make a decision from. Then we need to consider just what ‘high’ and ‘low’ mean out of context. Take a sirloin steak for example, 100g will contain around 5.1g of saturated fat which leads it to have a red traffic light, but foods don’t only contain one kind of fat; there is also around 5.4g of monounsaturated fat in sirloin steak which is shown to be beneficial to health. Not to mention what we saw in module 2 regarding the complexity of saturated fat and the health impacts which it can have, and of course that needs to be placed in the wider context of a full diet.

The red lights could lead people to go for ‘all greens’ for the whole day, which would then lead them to under consume saturated fat by effectively avoiding it. Labelling some things as red will of course cause people to avoid them completely by associating them with ‘bad’ or ‘stop’ and this is rarely a good way to view things.

This states a portion but doesn’t really go further than that, meaning that you need to engage critical thinking. A portion is not the same for a 50kg sedentary female who wants to lose weight and a 120kg male athlete, so these guidelines may not always be fully appropriate. This is especially the case when it comes to snack foods where a 220kcal ‘portion’ may represent 5% of the latter individual’s total calorie intake, but perhaps 15% of the former’s. With that said, a portion guideline for non-snack foods (cheese and pasta being prime examples) isn’t a bad place to start.

Finally, there’s the somewhat obvious, yet rarely spoken about issue which is present here. A low-fat ready meal made with processed meat, refined carbohydrates and little micronutrients could easily have a fully green label, while a highly nutritious steak, pack of eggs or indeed a packet of almonds would get reds for fats and possibly saturated fats. A pasta salad void of protein would also qualify as a healthy lunch by getting all greens, but a roast chicken salad with hummus may not. Which do we really think is likely to be more beneficial for overall health and weight maintenance considering all we know?

Sweets would get a red for sugar, but a green for everything else, and so would golden syrup. Clearly this system has a ton of utility but it’s completely insufficient to base your entire decision on when looking at foods. We would recommend using this system for those who are not yet ready to look into the science of nutrition and are simply trying to make better choices when starting out with improving their lifestyle. It can be a useful tool for judging snack options, so long as you are mindful of what your personal portion size should be. The reason for this is that a food may have what seems like a small amount of added sugar per portion but because the sugar content is calculated on a per 100g basis you can use this to compare it to other options.

In summary, while it is useful this area of the label, it is insufficient to give you the information you need to make fully informed choices from.

Before we move to the back of the pack, let’s look at something else which you’ll often see on the front of packaging, certain health-based claims. It’s not uncommon to see words like low-fat, light, lighter, high in fibre, low in salt. It may or may not surprise you to know that these have specific and defined meanings in line with what we mentioned before about labelling regulations and the strictness of the labelling laws. So, what else can you find out from the front of the packet?