How are habits formed?

Of course, this raises more questions than it answers. How does a person go from consciously deciding to do something, to running on autopilot and performing complex sets of actions without thinking? In fact, what does it mean to do something without thinking about it anyway?

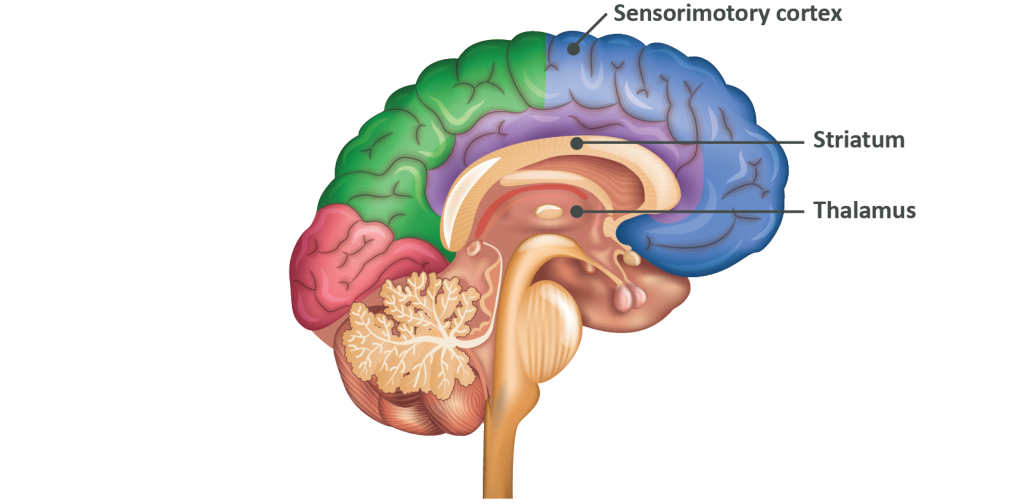

To fully explore these questions, we need to turn back to neuroscience and discuss some key areas of the brain. Three broad areas which you need to consider for this module are the basal ganglia – specifically the striatum, the orbitofrontal cortex which is a part of your frontal cortex and the sensorimotor cortex. They have the following loose functions:

- The orbitofrontal cortex is a part of the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain best considered to house ‘consciousness’ and executive function). It is chiefly res-ponsible for goal-seeking behaviour, meaning that you use your orbitofrontal cortex to internally debate the correct course of action in a given situation and then act appropriately. Damage to the orbitofrontal cortex leaves individuals behaving impulsively and without restraint, and it becomes very active when acting to bring yourself closer to something that has perceived value (of any sort). Individuals with Tourettes, drug addictions and OCD display reduced activity in the orbitofrontal cortex

- The sensorimotor cortex is comprised of the somatosensory cortex, responsible for the processing of somatosensory input (for example the tactile stimulus which you will receive if you touch something) and the motor cortex is used for performing physical movements. For this discussion, we are primarily focused on the latter of these two

- The striatum is a part of the basal ganglia. It sits deep within your brain and is heavily involved with dopaminergic reward, after being fed in to by numerous areas of the brain including the prefrontal cortex (which includes the orbitofrontal cortex) and with motor planning. The striatum has three areas which are especially relevant to this module – the area involved with goal seeking, that involved with habit formation and execution, and the area involved with reward (via communication with the dopaminergic reward centres in the midbrain)

The formation of a habit occurs via the following process:

- A new behaviour is explored. The prefrontal cortex including the orbitofrontal cortex communicates with the striatum regarding what is going on (while the sensorimotor cortex is active because you are moving). The area of the striatum involved with goal seeking communicates with the midbrain to release dopamine, and then back to the orbitofrontal cortex to reinforce behaviour which ‘works’ In our example, your orbitofrontal cortex decides to have coffee and so instigates a series of actions in the sensorimotor cortex. It also tells the striatum what’s going on, which then sends positive signals back to the orbitofrontal cortex to let it know that what it’s doing is ‘good’

- Habits start to form. Gradually the area of the striatum involved with habit formation creates a feedback loop with the sensorimotor cortex to bracket the rehearsed series of actions used in the newly explored behaviour together. By doing this it removes the need for the orbitofrontal cortex to remain so engaged in the task Your coffee making process starts to become more automatic. You no longer have to work out how much coffee you want to add, how much hot water, how long to let it brew or whether or not you want milk

- A habit is formed. As the connections between the habit-related area of the striatum and the sensorimotor cortex become stronger, those linking the goal-related area of the striatum and the orbitofrontal cortex get weaker. Once this has happened, instead of your entire orbitofrontal cortex communicating with your striatum to cause an action, a tiny part of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex known as the infralimbic cortex recognises a cue then ‘remembers’ that a task was once tied to both this cue and something you value, so it just ‘runs the program’. You effectively act on autopilot as soon as a cue is encountered

Eventually, you wake up and make a coffee without thinking and without even really working out whether or not you want one.

In short, as soon as you see the cue, your infralimbic cortex recalls what the reward was that is associated to that cue, and then it simply runs the chunk of associated behaviours necessary to get it, without even ‘consulting’ the orbitofrontal cortex – the area of the brain which would tie your actions to a goal.

This was discovered thanks to an enormous body of work undertaken at MIT using rats.