How the neuroscience of habit formation was discovered

In an extensive series of experiments conducted by Ann Graybiel and colleagues, rats were trained to run through a T maze.

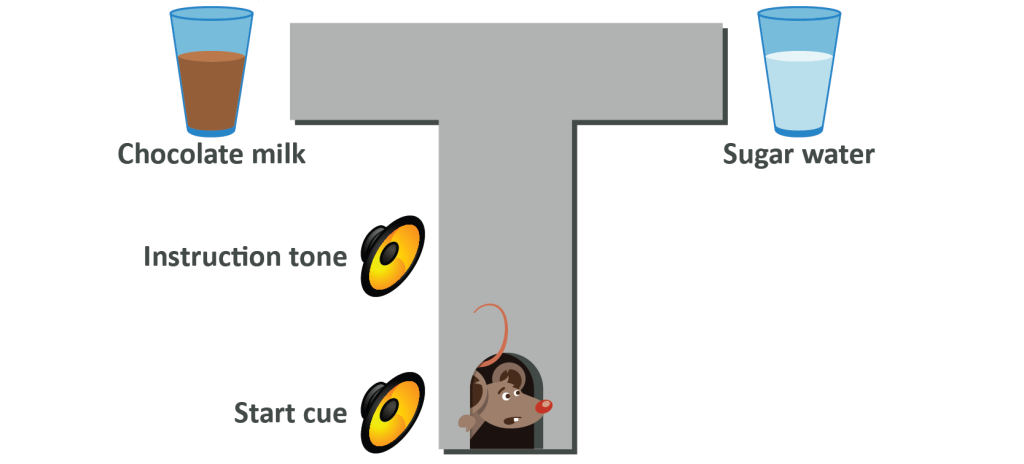

The rats heard a start cue, a gate opened and they were allowed to run along a path. Shortly before reaching a T junction they heard a specific noise. If they turned the correct way according to the noise they would get chocolate milk, if they turned the wrong way they would get nothing. After sufficient trials the rats turn the correct way each time. In the next phase the chocolate milk was removed and sugar water was placed at the end of the other T junction branch. The noise was also changed. Again, after a lot of runs the rat turned the correct way upon hearing the noise and got its reward.

In the next phase both drinks were placed in the maze and sure enough, the rat turned the correct way depending on the noise, meaning that the rat didn’t just learn that any noise meant a treat, it meant that it knew noise A meant turn left for chocolate milk and noise B meant turn right for sugar water. This experiment was conducted hundreds of times in order to imprint the behaviour as a habit – as evidenced by two different things.

First of all, the researchers recorded brain activity in the rat as the above image shows, with the patterns seen following a reliable and predictable pattern. In the initial stages, the striatum of the rat was hugely active – it was communicating furiously with the prefrontal cortex because new activities were being explored and the rat needed to know whether those activities were good or not. As the experiment was repeated further, however, it was seen that the activity in the rat’s striatum became far less pronounced; only really showing when the rat needed to make a decision of which way to turn, and shortly before receiving an expected reward. Eventually activity was almost non-evident other than at the beginning and end of the run, displaying that the behaviours involved with running and choosing a direction had been tied to the cue of the noise – the rat no longer thought about where to go, it just went with its habit.

How do we know that this was a habit, and not just the well-trained response of a rat that knows it gets a reward for running in the correct direction? In the next phase the rat was left in its cage and given chocolate milk at will. Each time it drank, however, it was injected with a drug which made it nauseous. After a short while the rat would associate chocolate milk with nausea meaning now chocolate milk was not tied to being a reward. Despite this association, the rat would still run to the chocolate milk upon hearing the correct noise. Critically, the rat didn’t value or want the chocolate milk (in fact it often wouldn’t drink it), it simply ran to it anyway because it wasn’t actively thinking, and was simply acting according to habit.