Sleep deprivation, more common than we think?

According to the Sleep Foundation, individuals need to get the following amount of sleep per night to be in peak health:

- Newborns (0-3 months): 14-17 hours

- Infants (4-11 months): 12-15 hours

- Toddlers (1-2 years): 11-14 hours

- Pre-schoolers (3-5): 10-13 hours

- School age children (6-13): 9-11 hours

- Teenagers (14-17): 8-10 hours (teenagers really do need to have a lie in!)

- Younger adults (18-25): 7-9 hours

- Adults (26-64): 7-9 hours

- Older adults (65+): 7-8 hours

This is unfortunate because according to the National Sleep Foundation Bedroom Poll of 2013 adults in the UK only get an average of 6 hours, 49 minutes sleep while needing 7 hours and 20 minutes. 51% report getting less sleep than needed on workdays, and only 42% report getting a good night’s sleep most nights. This is the average and it’s not great, but what happens if you get progressively less sleep?

Sleep deprivation is a complete lack, or suboptimal amount of sleep either acutely or over a long period, though sleep restriction is probably a more accurate term for incomplete rather than completely absent sleep.

As you read earlier, sleep occurs in cycles and each individual’s cycles will last 90-120 minutes or so. In order to have a full, restful night’s sleep the ideal situation is to have the correct number of cycles for you (usually 4-5) and allow them to run to completion. Waking up and feeling tired is one obvious sign of some degree of sleep deprivation but this could in fact have multiple causes:

- You are indeed sleep deprived, therefore you have not undergone enough stage 3 sleep to allow the complete clearance of adenosine, and so you still feel fatigued

- You are indeed sleep deprived and although you had the optimal amount of sleep last night you have built up a sleep debt over time to mean that you need multiple nights to catch up

- You are not sleep deprived, but in fact woke up during non-REM stage 2 or 3 sleep and therefore experiencing sleep inertia which will pass. This is the cause for the often made claim that people have slept too much, and why you may wake up at 5am and feel great (because you woke during REM sleep), but fall back asleep until 6:30am when your alarm goes off and feel terrible even though you have slept for longer. This sleep inertia typically dissipates after up to 30 minutes

This also goes the other way, if you have woken up feeling great but have not slept for long, you may have simply woken during REM sleep at the appropriate time of day and, according to your circadian rhythm you will wake and feel alert. This is often short-lived, however, and you are likely to feel a great deal of sleep pressure earlier in the day than you usually would. In general, sleeping from 7-9 hours as an adult is needed, though of course there will be outliers at either end of that range. Aiming to sleep well for this duration is the most effective way of avoiding sleep debt and it can be assumed that sleeping for much less than this will lead to a degree of sleep deprivation even if you subjectively feel OK (especially if you habitually drink caffeine upon waking).

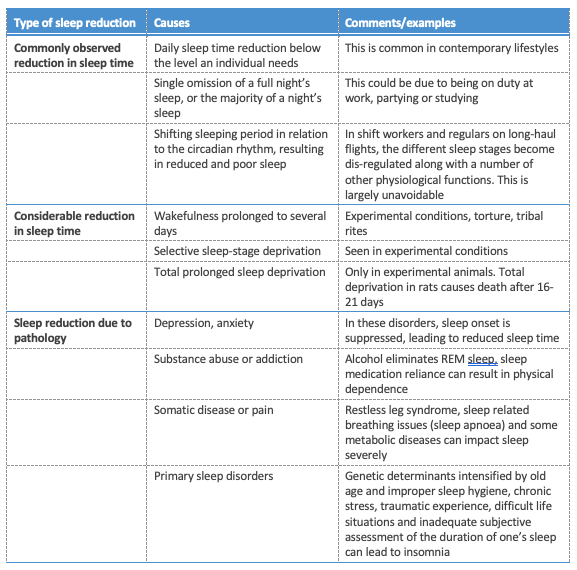

There are three primary causes of sleep deprivation as detailed below:

The longest recorded period of sleep deprivation in a volunteer study is 203 hours (around 8.5 days). During this period, the subjects showed a complete lack of usual alpha wave function, and in fact waking brainwave activity resembled that of stage 1 sleep. The longest period of wakefulness on record at the time of writing is 268 hours, held by a 42 year old man from Cornwall, England.

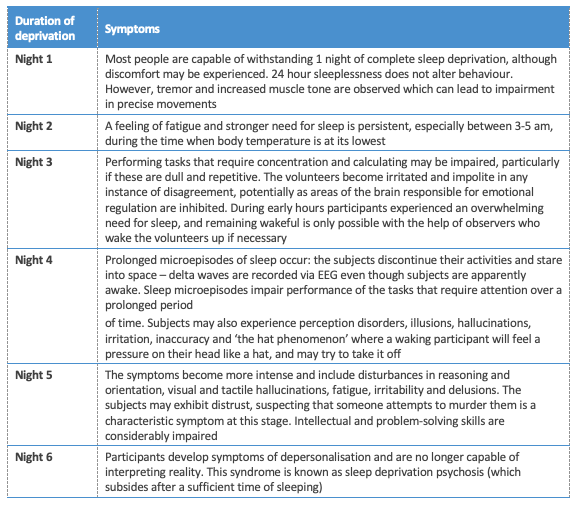

While this is extreme, multiple-day waking experiments have been performed with some amount of regularity. The results from one can be found below:

Most people will never be awake this long. In fact, it would be very unusual for someone to stay awake for more than 36 hours at any point in their lifetime (skipping 1 full night of sleep) but recent research has indicated that alterations to behaviour and experience accumulate across days of partial sleep loss, resulting in symptoms similar to those associated with acute 1-3 day restriction.

This topic is enormously complex because, as you have seen, sleep is not uniform and therefore when people are restricted to shorter than optimal amounts of sleep, each stage is differentially affected. Adults restricted to 4 hours sleep per night experienced a reduction in non-REM stage 2 sleep and REM, and almost absent stage 1 sleep but experienced no difference in the duration of non-REM stage 3 sleep, and actually saw an increased intensity of it compared to those sleeping 8 hours. With that said, this did not mediate cognitive impairment or other symptoms of sleep deprivation.

Additionally, there is data to suggest that while the range of 7-9 hours may be ideal and while reducing sleep to 6 hours will impair subjective ‘freshness’ upon waking, after a short time this effect disappears and there are no other symptoms, indicating a form of adaptation.

On top of this complexity is a sparsity of actual data. While studying complete sleep deprivation is comparatively simple, to perform experiments to test cumulative sleep debt, subjects would need to be monitored for 24 hours per day for 1-3 weeks in a lab. Because of this, only a few studies have been done. What must be noted, however, is that before these studies were done, anecdotal research suggested that the real sleep need was 4-6 hours of ‘core sleep’ and that anything beyond this was optional. More recent data, what little of it there is, refutes this. Daily insufficient sleep, contrary to older belief, gradually amounts to a sleep debt with the following symptoms.

An increased tendency to involuntarily fall asleep

This is probably the most obvious result of sleep insufficiency, but it causes you to find staying awake difficult. There is a dose-response relationship starting at around 6.75 hours per night of increased risk of falling asleep, with risk increasing as hours of sleep decline. This is accompanied by oculomotor activity alterations, with involuntary eye closure and eye rolling being part of the initial sleeping transition. The less sleep you get, the more often your eyelids will ‘force’ themselves closed which has obvious consequences for driving but also performance on tasks involving vigilance.

Behavioural alertness and cognitive performance

Performance on tests for psychomotor vigilance (a sustained-attention, reaction-timed task) is so sensitive to reduced sleep that your score on these tests is used as a marker of fatigue. Sleep deprivation increases behavioural lapses during performance which increase in duration from 0.5-10 seconds, and are thought to reflect ‘microsleeps’. These microsleeps are thought to reflect wake state instability, and are likely caused by the action of adenosine on neurotransmitters such as dopamine associated with maintaining wakefulness. Again, these can be exceedingly dangerous when driving.

In one study on truck drivers, those restricted to 3, 5, 7 or 9 hours in bed had their reaction times tested and those in the 3 or 5 hour group displayed a marked decline over the 14 day testing period. Another study kept participants in a lab for 20 days, and for 14 consecutive nights they were only afforded 4, 6 or 8 hours of sleep. Not unsurprisingly the 4 and 6 hour groups (but not 8) displayed a poorer performance on psychomotor vigilance tests and reduced cognitive output. What may be surprising, was that when compared to the effects of complete deprivation the results seen were equal to up to 3 nights of complete sleep deprivation, meaning that even though the participants were sleeping somewhat, their sleep debt quickly amounted to a far more impactful level than might be intuitively expected.

Subjective sleepiness and mood

Interestingly, while performance in various tests of reaction time and cognitive performance drop off relatively quickly from long-term sleep restriction, subjective sleepiness and mood do not. Complete sleep deprivation for 1-3 days and chronic sleep restriction both result in similar levels of cognitive impairment but while the former also comes with extreme levels of sleepiness and pronounced impacts on mood, in the latter subjects only report moderate levels of sleepiness. This indicates that it is very easy to underestimate the impact of sleep restriction and overestimate your readiness for performance at complex tasks.

Driving performance

As has been hinted at in this section already, sleep restriction severely impacts driving performance (real world and simulated for experimental purposes). Driving performance has been shown in numerous studies to be severely decreased (meaning more crashes) with sleep being restricted to 4-6 hours per night.

Altered appetite

Appetite is not something often thought about or considered to be ‘real’ but this is a mistake. Far from being a subjective phenomenon, appetite is a physiologically mediated process governed by your endocrine system. Two of the most impactful hormones for appetite are grehlin, considered to stimulate hunger, and leptin, considered to mediate general appetite overall. This can be conceptualised as such: leptin controls your background hunger to keep you at a given energy balance (it is leptin which decreases day-to-day when you lose fat beyond your set-point, and this is what initiates a lot of the fight back against dieting) and grehlin acts to induce acute hunger at meal times. With sleep restriction, overall leptin secretion is suppressed which in turn can lead you to adopt a higher set point, while grehlin secretion becomes more regular and far greater upon secretion. All of this means that sleep restriction causes a greater amount of hunger, a mechanism supported by the epi-demiological evidence that low sleeping hours are correlated closely to obesity and diabetes. Increased BMI is correlated with poor sleep in individuals as young as 3-8 years old.

Impaired decision making and self-control

One of the areas of the brain most strongly affected by sleep restriction is the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for personality expression, planning complex cognitive behaviour and decision making. Because of this, sleep restriction makes it far harder to avoid acting on impulse which, when combined with the above appetite alterations, can severely impact your success with controlling your food intake.

Immune response

It is relatively well documented that complete sleep deprivation impairs immune function but the impacts of restriction on the immune system are at present poorly studied. What can be taken from the limited research is that sleep restriction to 6 hours per night results in an increase of IL-6 in both sexes and TNF-alpha in men, both of which are markers of systemic inflammation. Systemic inflammation is associated with insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis, so this should not be ignored.

Cardiovascular health

Epidemiological (observational) studies indicate an increased risk of cardiovascular events when sleep is restricted to less than 7 hours per night but as yet no direct mechanism can be noted; there are too many co-variables such as a relationship between poor sleep and weight gain.

Muscle growth and loss

Sleep restriction alters the secretion patterns of testosterone, estrogen and cortisol negatively, as well as that of growth hormone (and therefore IGF-1 which is related to GH). This can result in an environment that promotes an increase in muscle protein breakdown and an impairment of muscle protein synthesis. Additionally, the restoration theory of sleep importance indicates that a reduction in sleep duration can impair the neural pathways which lead to muscle contractions and therefore exercise performance. This all adds up to meaning that exercise performance and recovery may be impaired, leading to far slower progress.

As you can see, the impacts of poor sleep can be far-reaching, but it would be a mistake to think that everyone will get every issue noted. Inter-individual variability in sleep requirements and circadian rhythm ‘settings’ is quite pronounced in some cases and this reflects on the responses that individuals experience when they don’t sleep as much as they ideally would. Sleep which is restricted to less than 7 hours leads to pronounced neurobehavioural alterations in most healthy adults but not everyone experiences issues in experimental conditions. Similarly, some people will experience severe effects with mild restriction while others will not experience any difference until restriction becomes severe.

Additionally, people will experience each effect to a different degree, so while some may find that their memory is profoundly reduced, but reaction time is unaltered, others may feel no sleepiness but notice that their reaction time is greatly increased. Interestingly and importantly, though effects change between people they seem stable within individuals across different instances of restriction and therefore become predictable, implying that they are inherent to that person’s genetic makeup.

Wherever you fall on the spectrum and whatever symptoms you experience, it should be self-evident that avoiding sleep restriction is a very good idea. Sleep, however, does not come easily to some, especially in the modern world in which distractions and daily stresses are high while sleep is looked upon almost as a waste of time. Of course, there are pathologies listed in the table earlier in this module such as sleep apnoea and insomnia, as well as interactions with medications which can alter sleep and the treatment of these is largely beyond the scope of this course, but there are general principles and activities you can do to give yourself the greatest possible chance of having sufficient, high quality sleep.