The nutritional values

On every food product which is not listed above as an exception, you will find the nutritional information per 100g of product, raw and uncooked. This may also be accompanied by information of either a portion (raw or cooked) or per unit (so per 1 biscuit or 1 slice, for example), but this is done by choice. The nutritional information is the absolute best place to look for information on the foods you are buying because it is here that you will be able to see how well a given food fits in to your overall nutritional approach. Each label must contain, in the following order:

- Energy in both kilojoules and kilocalories

- The fat grams

- The saturated fat grams

- The total carbohydrate grams

- The sugar grams

- The protein grams

- The salt content<

In addition to this, you may also see monounsaturates, poly-unsaturates, polyols (a lower calorie sweetener), starch, fibre and any of the vitamins and minerals spoken about in module 3, including sodium. If these are listed the vitamins and minerals must be included alongside the absolute amount as well as the % of daily need, and the other nutrients must be given alongside the gram amount.

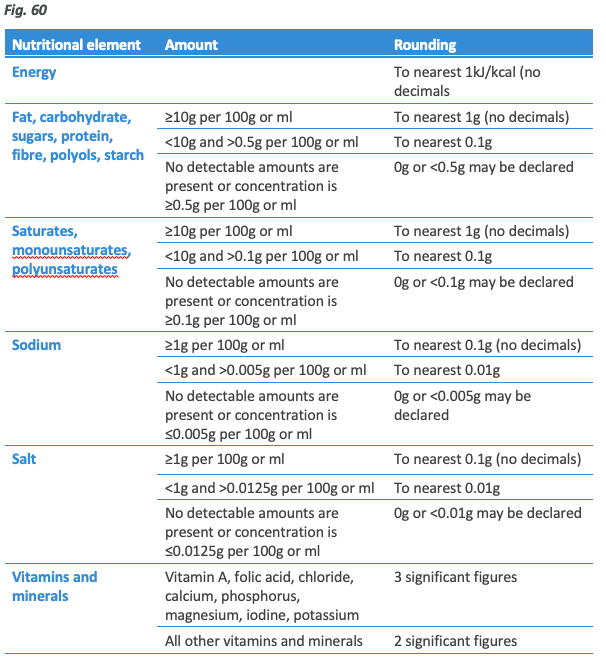

Finally, many nutrition tables will quantify all of the nutrients by either giving a percentage of the guideline amount (for a female), or simply listing the guideline amount and letting you work it out yourself.

These will be presented on the label in a table format, similar to this:

Important notes on nutrition table labelling

Vitamins and minerals can only be listed if they are present in a ‘significant amount’ because most multi-ingredient foods will contain a lot of trace nutrients which aren’t highly present enough to matter. This means that it must contain at least 15% of the reference value per 100g/100ml for foods or 7.5% per 100ml for beverages. If a single serving is assumed to be less than 100g/100ml then the food or beverage must contain 15% or 7.5% respectively of the average daily requirement per actual serving. For example, if cheese is to have calcium listed on the label it must contain 15% of your daily calcium requirement per 30g portion, whereas milk can make this claim so long as it has at least 7.5% of your daily need per 100ml.

Companies are not allowed to declare anything else including trans fats or cholesterol, so this will not be on the label. As mentioned in module 2, dietary cholesterol isn’t really something to be concerned about, and as you saw above you can locate trans fats in the ingredients list.

In some instances, a product may claim to be high in, for example, Omega 3. If this is the case then the nutrient must be listed somewhere on the label along with the total amount.

How accurate are these?

Intuitively you may have noticed that this labelling is phenomenally useful, but that it may be difficult to get right. After all, it’s surely not possible for every chocolate chip brownie to have the exact same amount of chips in, it can’t be right that every bag of crisps has the same crisp count and surely an apple grown in the middle of a field will have absorbed slightly different amounts of nutrients to one grown on the edge of a field where the feed perhaps didn’t quite reach so well?

You’d be correct.

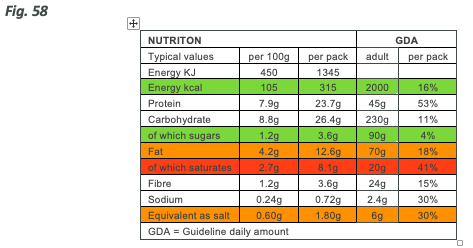

Seasonality, degradation of nutrients between picking and packing, differences in soils or plant/animal feed, animal genetics and diet, homogeneity of pre-packed and batch-cooked foods and many, many more elements make it simply not possible for every single packet to contain the exact amount of energy and nutrients as every other, and that is why there are acceptable tolerances in food packaging which vary based on the nutrient concerned. These are listed below:

Here you see that each nutrient has a range of different error tolerance levels depending largely on the total content of those nutrients. Taking carbohydrate as an example, we see that a product which contains less than 10g per 100g is allowed to be ‘out’ by 2g up or down, and then this scales with the total inclusion.

This could mean that a product which has 35g protein listed on the label could have up to 42g or as little as 28g, which is quite a difference. This also impacts the energy content of the food, too, as an incorrect inclusion of protein and carbohydrate by the upper end of the tolerance level could represent a significant amount of calories per portion over the course of a day.

This doesn’t invalidate food labels or make them useless, but it does tell you that it’s not worth being extremely concerned about ensuring you meet your requirements exactly from label information.

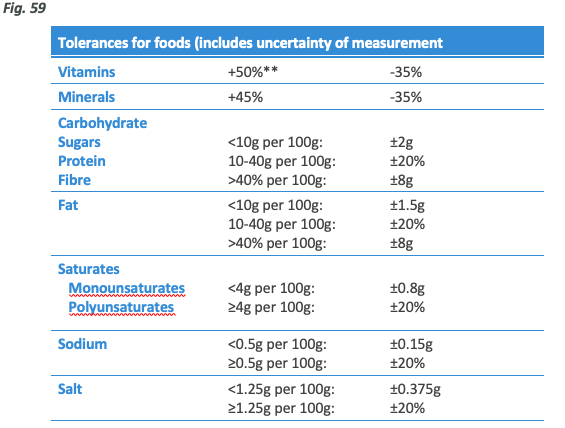

Lastly, most labels are rounded as it’s unlikely something would contain exactly 10g of fat, though that may be listed. The rules around rounding are here for completeness: